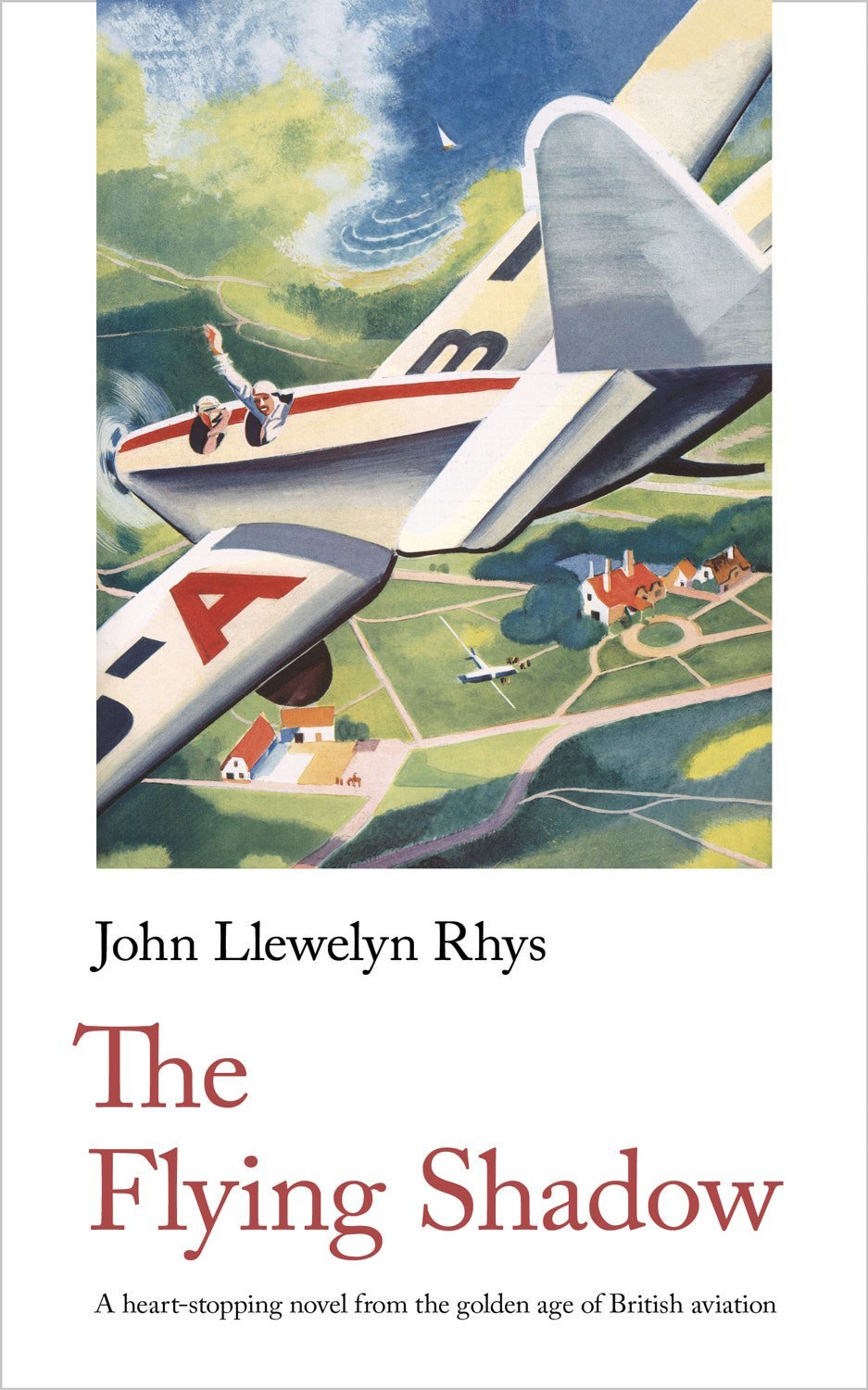

The Flying Shadow by John Llewelyn Rhys

Review by Cath Barton

If people today know the name of the Welsh author John Llewelyn Rhys (1911-1940) it is more likely to be for the prize set up in his memory by his widow Jane Oliver than for his novels. Now republished by Handheld Books in their series of forgotten classics, The Flying Shadow (1936) is a novel set in the relatively unexplored territory of early British aviation.

In Rhys’s novel, pilot Robert Owen takes a job at a flying school in an English cathedral town, where he teaches all comers. This reflects a huge – but little explored in fiction – interest in the relatively new technology of aviation amongst the British population in the 1930s. At the time, Rhys’s work was compared to that of his French near-contemporary Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, best known for his novella Le Petit Prince (1943) but, like Rhys, an aviator who also wrote books about flying.

In common with the other novels in the Handheld Books series on twentieth century history, The Flying Shadow focuses on individuals and their lives. So while it is rich in technical detail about early light aircraft, the novel is primarily about what a life dominated by flying is like for Owen and his colleagues at the flying school. The shadow of the title is not just that of the plane on the fields below, but that cast by a war not long past (and another approaching).

When Owen tells his father about the job that he is leaving home for, the clergyman says: ‘You have to work and you must do what you like. After all, it’s your life. Only be careful.’ But being in a ‘tiny room in the clouds’ is an obsession for Owen, an obsession that embraces danger. As one of his colleague says to him: ‘God alone knows what blokes like us did before men flew.’ And alongside the dangers in their work are those of the heart. Owen claims to be cynical about love, but when he takes on his first woman pupil he is drawn by her beauty as much as he is by the beauty of the skies. She, though, is married.

Rhys’ hero is shy but dashing. It is not surprising that he – and his conversations with the woman, Mrs Hateling – recall Trevor Howard playing the doctor in David Lean’s Brief Encounter. Noel Coward’s one-act play on which the film was based, Still Life, is exactly contemporaneous with the first publication of The Flying Shadow, and indeed the day-to-day lives of the couples in both are separated by a train journey.

The tentative romance between Owen and Mrs Hateling is a major element, but ultimately less important to the narrative than flying, and it is the descriptions of this, and in particular of the countryside as seen from above, that stand out in Rhys’s writing, as here: ‘It was a dim winter day and they flew for two hours through the cold, mist-woven air; watching the unreal world, pierced by the glitter of railways, merge into the peaceful sky, while pale rivers and smoke-hooded villages flowed beneath and the clouds echoed to the beat of their engine.’

If the narrative is sometimes a little choppy, and Owen’s philosophical musings verge on becoming didactic set pieces, there is nonetheless something compelling about Rhys’s storytelling. His passion for that world shines through. Tragically, both he and Saint-Exupéry died, too young, in flying accidents. Were they reckless or just unlucky?

At the end of The Flying Shadow, for all that has happened, for all those who have crashed and lost their lives, Robert Owen’s life goes on. It is good that the book does, too; it is not just a nostalgic curiosity, but an important piece of the social history of Britain in the 1930s.

The Flying Shadow is published by Handheld Press, 15th November 2022