In Brief - October’s Best New Books

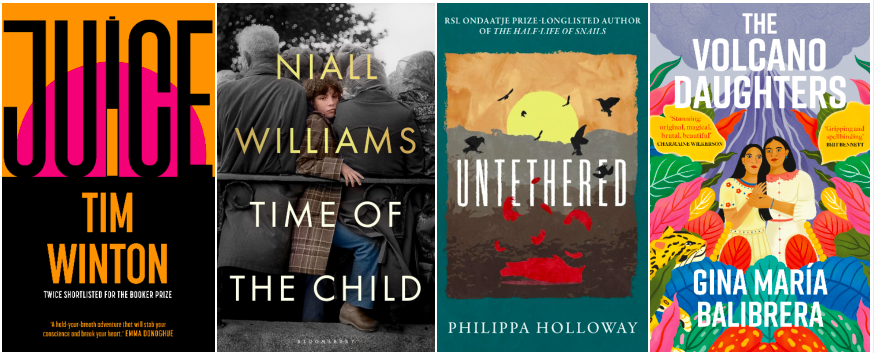

(Juice by Tim Winton

(Picador, 528pp)

From the Australian writer perhaps still best known in the UK for his family saga Cloudstreet, comes an unexpected change of mode: Juice is an epic in every sense of the word, a tale of a broken Earth, set several hundred years in the future, and told in flashback by an unnamed narrator. Guarding a similarly unnamed young girl, he enters a seemingly abandoned mine to escape the brutal desert heat, only to become the prisoner of ‘the bowman’. To buy time, he begins to tell his story: of decades spent working across Australia and beyond for the Service; of his missions, during the few months of the year when humans can safely come above ground, to track down those responsible for the dystopia visited upon the planet by fossil fuel excess; of how and why he came to be in the service of his mysterious charge. Credit to Winton for just how pointedly he nails those responsible for his story’s future — and our current — environmental catastrophe, and the premise is genuinely intriguing, but the novel surely would have benefitted from equally brutal editing: at over five hundred pages, with much of that weight borne by extremely detailed description of the narrator’s many missions, it quickly loses its page-turner potential and trudges to its frustratingly ambiguous ending.

Time of the Child by Niall Williams

(Bloomsbury, 299pp)

Fans of Niall Williams’ previous novel, This is Happiness, will find much to admire is his latest. Once again, the acclaimed writer returns to the village of Faha in the west of Ireland and centres his Chistmas-set tale in and around the lives of its doctor, Jack Troy, and his adult daughter Ronnie. As the locals prepare for the holidays, disruption arrives in the form of a baby, abandoned, discovered by young Jude Quinland, and left in the Troy’s care. Given the name Noelle and ultimately coming to unexpectedly attend to many of the tender spots that have grown in this father-daughter relationship, the novel itslef peforms a quiet miracle as it swerves the sentimentality that might hobble such a narrative. Instead, Williams, who writes with a quiet exactitude, and no little command of poetry — ‘The wind’s marriage to the rain gave birth to a third weather that could quench the candles of whatever it was that that kept you living and required countering’ — guides his gentle story towards a moving, and entirely convincing ending. A Christmas miracle, indeed.

Untethered by Philippa Holloway

(Parthian,156pp)

Untethered follows Philippa Holloway’s 2022 novel, the Chernobyl-set The Half Life of Snails. A writer with a distinct grasp of both the long and short form, this debut collection has been compiled largely from previous publication, with the addition of the a handful of new stories. Indeed, one of the heftier pieces here, ‘The Weight of a Shoe’, was first published by Lunate. That story remains a rangy delight, but there is much here to recommend your time and investment, not least ‘The Message’, in which the appearance of a bird in a family’s house casts ominous shadows, and the flash piece ‘Beached’, in which the narrator’s response to a stranded octopus serves to expand the story some distance beyond its handful of pages. Gripping throughout, and delivered in effortless, understated prose, Untethered confirms Holloway’s narrative gifts: namely, her way with a story and her convincing humanism.

The Volcano Daughters by Gina María Balibrera

(OneWorld, 356pp)

In the El Salvador of the 1930s, a tale of two sisters. One, Consuelo, stolen by the dictator El Gran Pandejo and taken to the presidential palace in the country’s capital, and the other, Graciela, later taken while nine years old, unaware of the existence of her sister until now. As they come to know each other and build new lives within the palace, a background of political uprising and a government-sponsored genocide give the tale both bite and relevance. Gina María Balibrera’s debut novel, which sees the girls navigate the disaster that follows by travelling to LA and then Paris, is, at times, as funny as it is unsettling, capturing both the trials of girlhood and the horrors of war. Narrated by a compelling ghost chorus (four women murdered during the earlier coup), The Volcano Daughters deserves plaudits for its stylistic invention, too, and marks out Balibera as a writer to watch.